Back in 2002, the Social Security Administration noted that, unless there was significant reform, the Social Security system would become insolvent by around 2041. In order to make up the shortfall, the government would either need to cut Social Security benefits by more than 25% or increase Social Security payroll taxes to more than 18%.

At the time, Robert C. Pozen, a senior lecturer at MIT Sloan School of Management and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, wrote in a Harvard Business Review article “because of the demographic bulge of working baby boomers, Social Security contributions exceed payments for the time being. This ‘surplus’ enables the government to mask what otherwise would be a much larger budget deficit. However, as the baby boomers retire, the demographics of Social Security will move in the opposite direction—adding to the overall budget deficit.”

We’re nearing that time. The last of the baby boomers will reach retirement age in 2031, resulting in roughly 75 million people over the age of 65 in the United States.

The implications of this milestone are twofold: Less money will be going into the Social Security system by way of payroll taxes, and more people than ever will be receiving Social Security benefits.

Despite nearly annual increases to the Social Security wage base (it was raised just over 3% for 2020 to $137,700), these increases have not been enough to ensure solvency in the future. In fact, the situation is a bit worse than those 2002 predictions set forth. The Social Security Board of Trustees’ 2020 annual report noted that the trust funds that disburse retirement, disability and other Social Security benefits will actually be depleted by 2035, six years sooner than thought in 2002.

So what does this mean for the future of Social Security?

First, it doesn’t mean it will no longer exist. Rather, the system will exhaust its cash reserves and so will only be able to pay out each year what it brings in. It’s estimated that, when this happens, the Social Security Administration will be able to pay roughly 79% of annual benefits due to recipients.

While that seems a surmountable shortfall, particularly if Congress acts to increase Social Security payroll taxes or reduce benefit amounts (or both), these projections in the 2020 annual report did not foresee the impact of COVID-19 and its potential long-term effects.

How COVID-19 will impact Social Security now and in the future

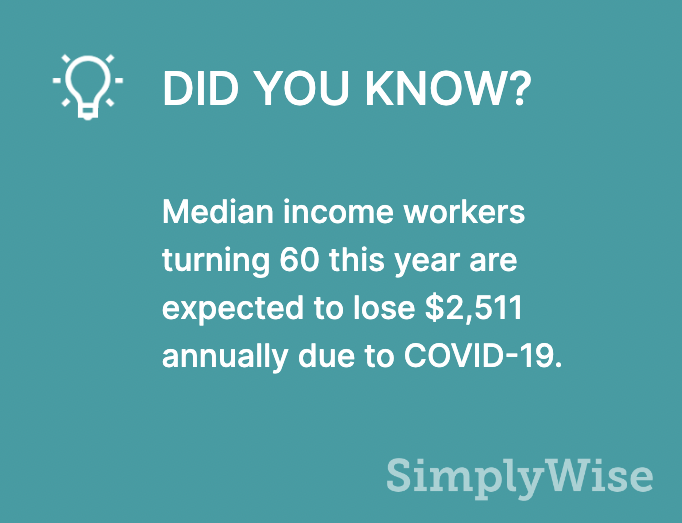

The economic downturn resulting from the pandemic will almost certainly result in a reduction in average earnings for 2020. That means less money into the Social Security system by way of taxes, but it also could result in a reduction in the indexed lifetime earnings for many people, especially those turning 60 this year.

Before getting into the full explanation of why, let’s quickly look at how Social Security benefits are calculated:

Your Social Security benefits are based on your lifetime earnings. The Social Security Administration adjusts or “indexes” your actual earnings to account for changes in average wages since the year the earnings were received.

Called the average wage index (AWI), this figure basically amounts to the total U.S. wages paid in a given year divided by the number of W-2 earners who report wages to the Internal Revenue Service. Before the pandemic, there was a record number of people employed in the U.S., but given mass unemployment since the pandemic, the total wages for this year will be significantly lower.

With this figure in hand, Social Security calculates your average indexed monthly earnings for the 35 years in which you earned the most. The resulting figure is your “primary insurance amount.”

Near-retirees could be hit hard

Here’s why all of this is going to impact people turning 60 this year especially hard: The higher the index in the year a wage earner turns 60, the bigger the adjustment for their basic benefit.

“Due to how the Social Security benefit formula interacts with the sharp economic downturn due to the Coronavirus, some groups of near-retirees are likely to suffer substantial permanent reductions to their Social Security retirement benefits, Andrew Biggs wrote in a recent working paper for the Wharton Pension Research Council.

Biggs, a former principal deputy commissioner of the Social Security Administration, and an American Enterprise Institute resident scholar, found that median income workers turning 60 this year will lose $2,511 annually. And that’s if they wait until the full retirement age of 67 to take their benefits. That’s a loss of $45,859 in total retirement benefits over an 18-year period.

On top of that, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for 2020 will likely be low or even negative. That will result in no cost of living increase (COLA) for Social Security benefit recipients in 2021.

Many will likely postpone retirement

Even before the pandemic, more and more retirement-age people continue working. In a poll from The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research, 23% of workers said they don’t expect to stop working ever. And new statistics show that people above the age of 65 are already working at all-time high rates since record keeping began. The May 2020 Retirement Confidence Index found that 67% of people today plan to continue working in retirement.

Fortunately, today’s seniors today are more physically healthy than ever. Also, better, more flexible and more fulfilling work options are now at their disposal through recent technological advances. Many seniors, realizing how much they have left to offer and discovering the ease of finding ways to get paid, are choosing to extend their careers into their retirement years and complement income coming from their own earned benefits, spousal benefits or survivors benefits.

As Pozen noted in his 2002 article, “If workers retire later, they can make significant contributions to American business. Older workers are often quite productive because they tend to have more skills and experience. Yet older workers may not be able to handle the physical demands of certain jobs as well as younger workers. And workplace tensions may arise, as younger employees perceive that their careers are being blocked by older employees who refuse to retire.”

The future of Social Security is not all bleak

As you look at all of these figures, it’s important to keep a few things in mind. First, there’s still time for Congress to take action, though the window of opportunity has narrowed significantly. Proposals to shore up Social Security have been debated for decades and typically fall into two categories: increasing Social Security taxes, reducing benefits or both. Unfortunately, agreement between Democrats and Republicans on what the future of Social Security should look like has been elusive.

Second, knowing your options is key to ensuring you maximize your benefit amount. As we explain in our guide to Social Security benefits, beneficiaries are rewarded with a larger monthly payment for every month they wait after turning 62 and until age 70. However, waiting to receive a larger monthly benefit also means forgoing retirement benefits during that time. With doubt around the solvency of the program, some may feel pressure to take the sure money earlier instead of gambling on the outcome of whatever policy is introduced. For others, speculation may impact decisions around work and collecting Social Security.

Each individual’s Social Security calculation is different, but fear or speculation about one outcome or another could dictate how people decide to apply for their benefits. Additionally, should talk arise around changes to how Social Security income is taxed, rules on benefits for widows and widowers or adjustments to spousal benefit eligibility, seniors may be inclined to change their claims strategies.