For the last 18 months, the Federal Reserve has been increasing interest rates. The last time this happened was over 10 years ago, which means that many people who began investing in the past decade have only experienced an economic environment of low or falling rates. The key question we’ll try to answer is: what is likely to happen to the bonds in your portfolio when interest rates rise?

Who Is Affected by Bond Price Changes?

Investors typically own a combination of bonds and some stocks; the typical mix is a 60/40 stock/bond portfolio. Investors who are closer to retirement tend to take less risk in their portfolios, meaning they tend to be more weighted towards bonds. They are more exposed to changes in bond prices. For younger investors, any volatility in the price of bonds they own will typically be lower than the volatility they are experiencing in the stock market.

How Interest Rates and Bond Prices Are Linked

To understand the effect of interest rates on bond prices, let’s assume that you buy a US government bond right when it is issued by the government. By doing so, you are loaning the US government money, and in return they will pay you an interest rate and promise to return your principal in 10 years. How much interest you are paid depends on the interest rate set on the bond when you purchase it. There isn’t too much complexity here. This experience of buying a bond and holding it until its term ends is fairly similar to the experience of buying a certificate of deposit (CD). You put some money in, and after a certain term you get back your original money plus interest payments along the way.

Where things get more complicated is if you try to sell the bond before the term is up. Let’s say you buy a 10-year bond from the US government that pays a 3% interest payment per year. Halfway through the term you decide to sell the bond. The amount of money you will get for the bond will depend on what interest rate someone could get paid for the remaining 5 years. If interest rates in the economy have gone up and you can now buy a new 5-year bond that pays a 7% interest rate, then it may be harder for you to sell your 10-year bond without incurring a loss. In other words, if you had to value your bond daily according to what you could sell it for, you would have seen its price decline.

The reason this matters is because a lot of investors get exposure to bonds through bond funds and ETFs that have to value their bond portfolios every day, thereby exposing their investors to gains and losses in the market value of the bond.

Historical Losses from Holding Bonds

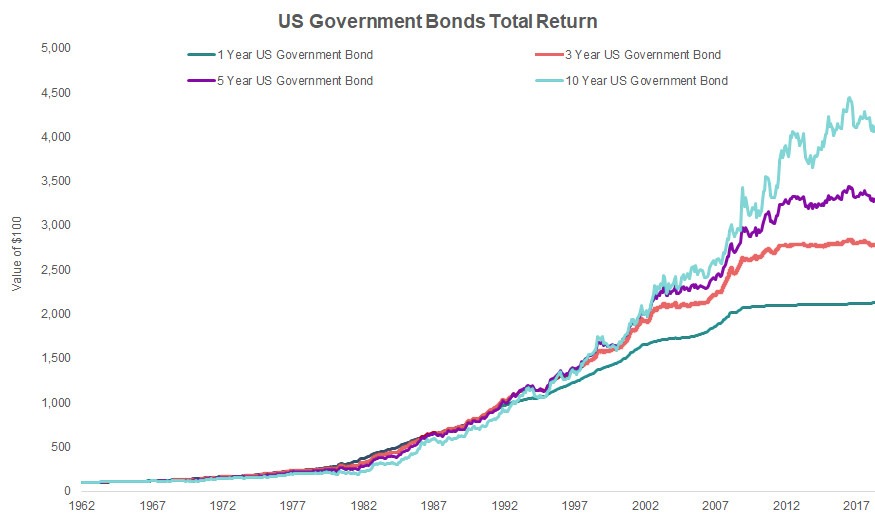

Let’s explore what these losses have looked like historically. We’ve gone back in time and generated total return series for a bond fund that holds US government bonds of a constant maturity of 1 year, 3 years, 5 years, and 10 years.

The graph above shows the value of $100 invested in bonds of different maturities. The first thing that stands out is that the 10-year bond is the most volatile. This makes some sense. Imagine you owned two bonds: one that had 9 years left to its term and one that had 3 years left. If interest rates increase, then both bonds will become less valuable (since you’d be able to buy new bonds for the same term with a higher interest rate). Which bond would you expect to become less valuable? It turns out the 10-year bond will drop further in price, because it is the one with more interest payments left that are now worth less.

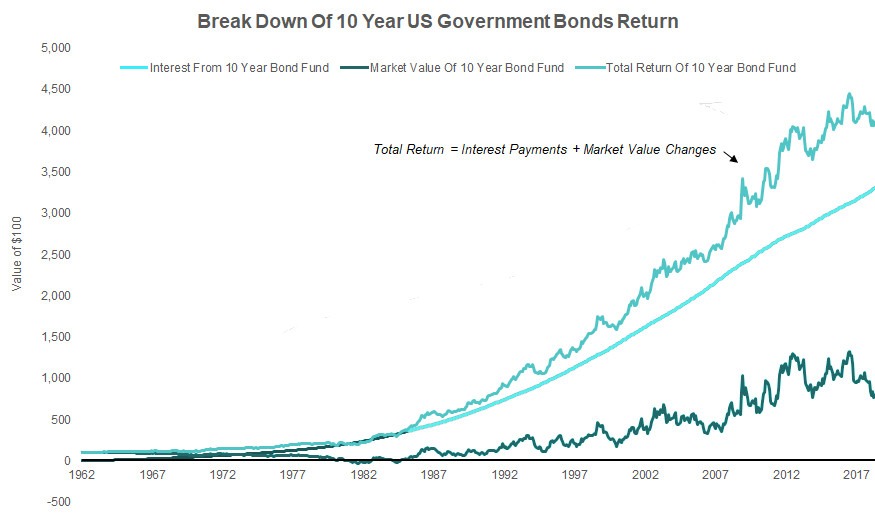

The volatility in the return stream comes entirely from the market value of the bond changing day to day. You’d expect your income from the bond to be relatively steady as the bonds continue pay interest to you. In the graph below, we’ve broken out how much of the total return of the 10-year bond comes from interest payments rather than from the fluctuations in the market value of the bond.

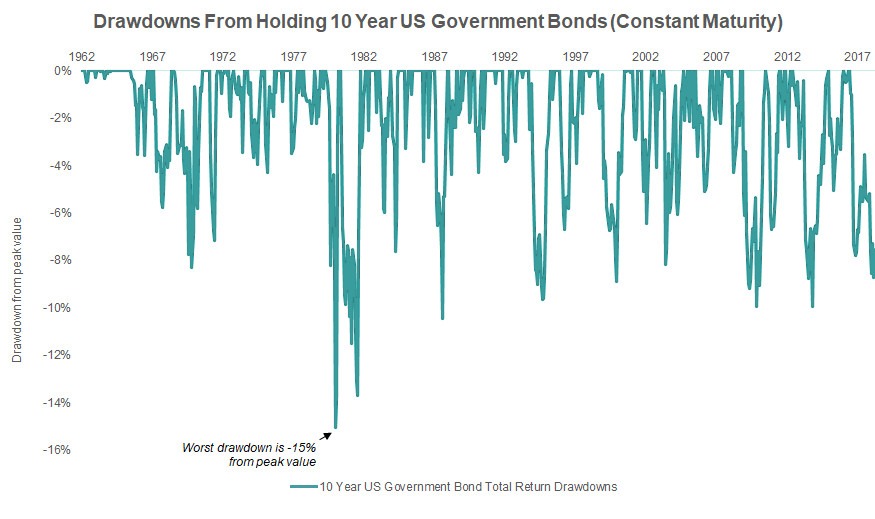

The next question you might have is: how big have these fluctuations been historically, and are they worth worrying about?

The graph below shows the drawdowns you would have experienced by owning a bond fund that maintained exposure to 10-year bonds over the past 60 years. A drawdown is how much you would have lost at any point in time from the peak value of your investment. Let’s say that you own shares in a bond fund that is worth $100. It then increases in value to $110, before dropping to $90. In this case your drawdown would be ($90 – $110) / $110, or -18%, meaning you would have lost 18% of your money from its peak value.

The graph shows that over the past 60 years you would have experienced a maximum drawdown of about -15%. There are 5 cases where an investor would have experienced a 10 percent loss in the value of their bond fund. For many investors who are young who have a large allocation to equities, these drawdowns are relatively insignificant when compared to the volatility of the stock market. However, for investors who see investing in bond funds as a relatively safe way to store and grow money, the fact that they can potentially lose more than 10% of their money might come as a shock.

In the next part of our series, we’ll look into novel ways to generate higher yields from bonds during periods of poor bond performance.